Stories and events of Black people and groups who have shaped Northern Colorado culture and history.

Since 1970, every sitting U.S. President has recognized February as Black History Month; since its inception, it has developed into a month of celebrating important Black and African American figures in history and also celebrates Black culture and heritage across the country.

This month, we honor not only the unique contributions of Black individuals who shaped the Northern Colorado area but also recognize the discrimination, prejudice, and challenges they have faced. We recognize the erasure of Black stories from American history and highlight some of the Black History that took place along the rich lands of the Poudre River in the Northern Colorado area.

Below, you’ll find stories and histories collected by the City of Fort Collins honoring those unique individuals and pieces of Black history that have been formative to the Fort Collins community.

The Lyle Family

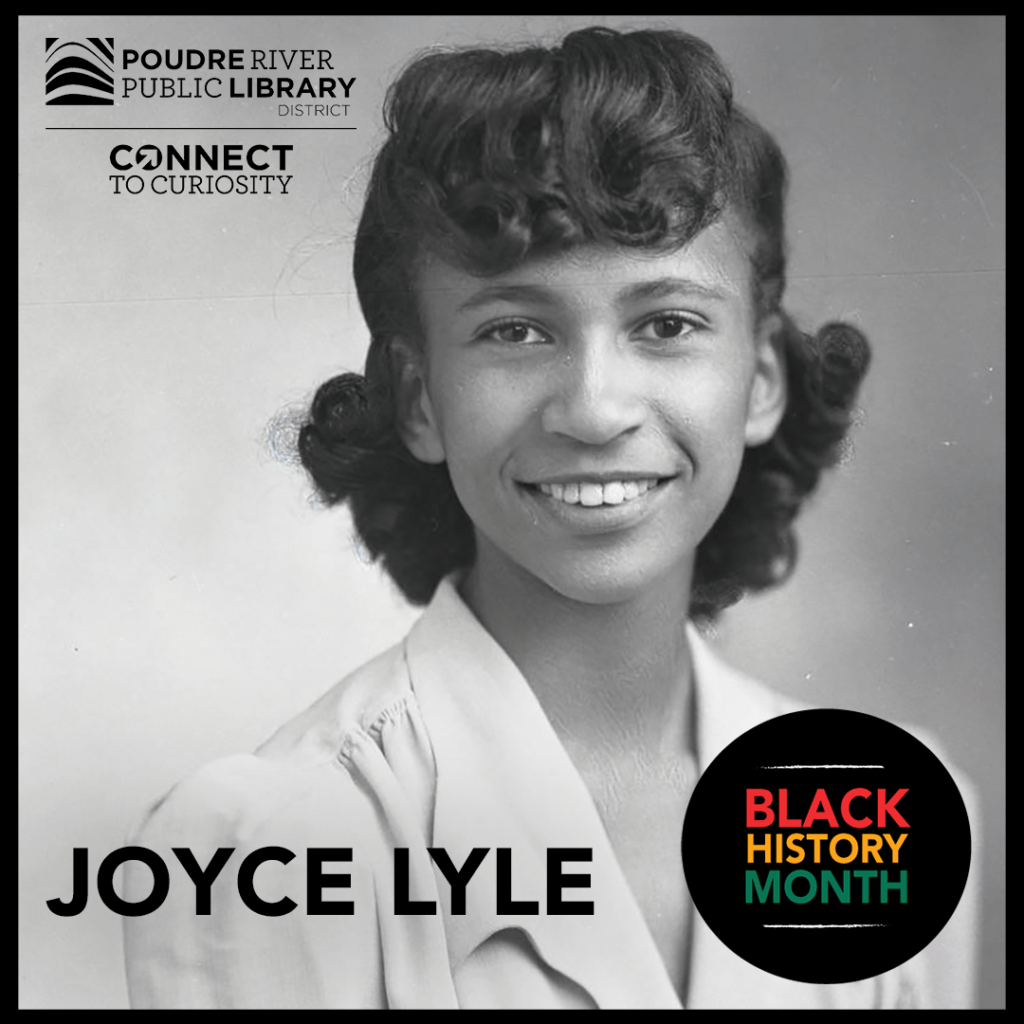

151 N. College Avenue, has been many things over the course of its life since its construction at the beginning of the 20th century. Today, we know 151 N. College Ave. as the Still Whiskey Steaks building. In the 1930s and 1940s, it was a theatre for movies and entertainment. For a brief time, it was known as the State Theatre. In the Spring of 1939, the theatre’s discriminatory practices against Black individuals eventually resulted in a discrimination lawsuit lodged by Mattie Lyle, a Black woman who lived with her family in Fort Collins at the time. She won her discrimination suit against the owner of the theatre, L.C. Snyder, in County court and was awarded damages in an era predating the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. This made the location a significant site for Black civil rights in the City of Fort Collins.

The testimony presented in court was supported by her husband (William Lyle), her 13-year-old daughter Joyce Lyle (pictured), and her friend Stella Saunders. The Lyles were a particularly important part of the Fort Collins community and have a long familial record of fighting for civil rights – the family eventually made their permanent home in Seattle, Washington.

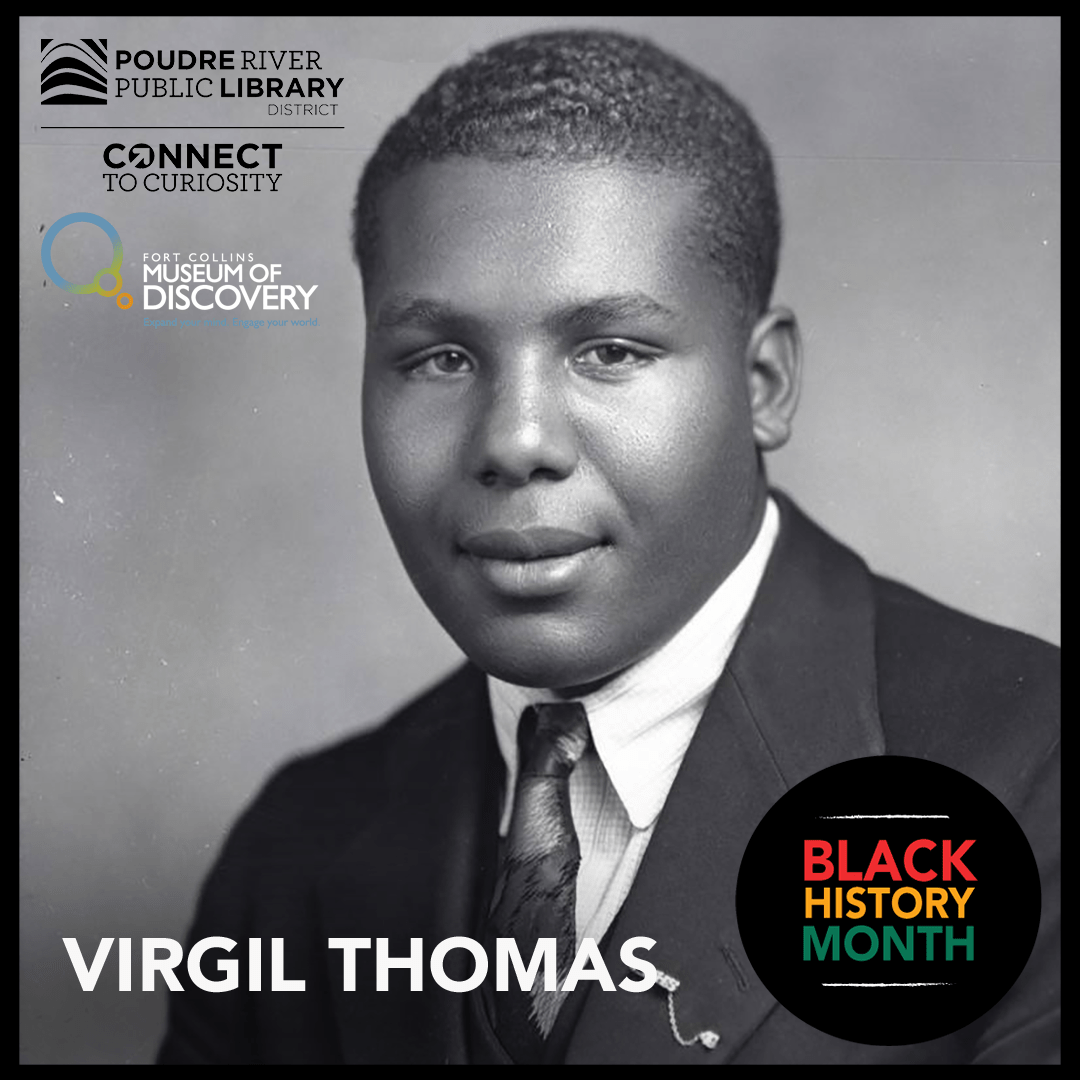

Thought to be one of the first Black students to graduate Fort Collins High School in 1940, Virgil Thomas was a star left tackle for the football team, a talented boxer and softball player, and would later go on to become an infantry corporal during WWII serving on the European front lines in Italy and Germany.

From the historical documents we have left today, it’s clear Virgil was well known across the Fort Collins area for his incredible abilities on the football field as well as being the only black player on the team. He graduated from Fort Collins High School in 1940; his athletic abilities prompted him to attend Wilberforce College in Ohio on a football scholarship. Virgil’s parents, John and Mamie, spent most of their lives in Fort Collins in a house on Cherry Street, an area that was previously an important black neighborhood.

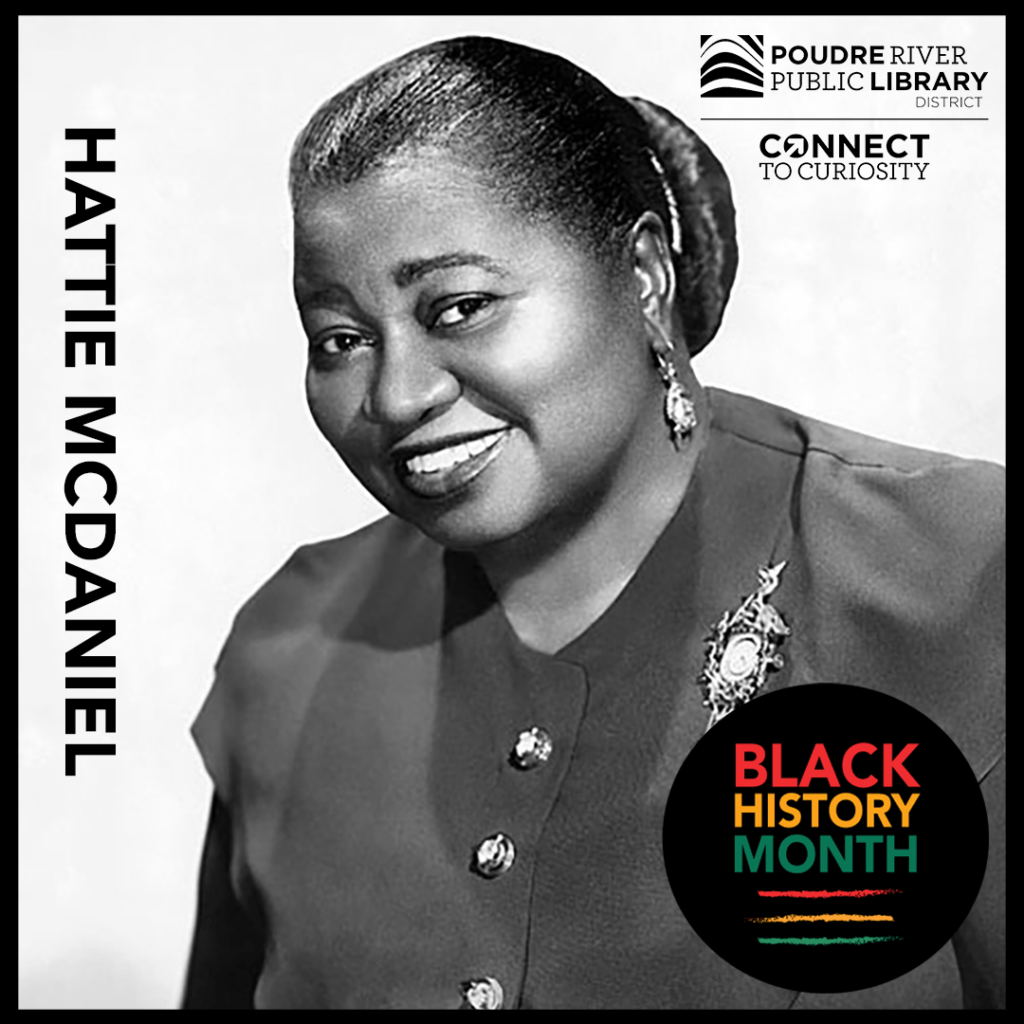

Hattie McDaniel and her family lived in Fort Collins for a very short time, though they are one of the most well-known black families in Fort Collins early history. Hattie’s parents, Susan and Henry McDaniel, were both enslaved at birth. They were also among the early wave of Black migrants who fled the Jim Crow South to Kansas to seek greater freedom and opportunities in the 1870s.

The family later moved to Denver, and for a brief time in the early 1900s lived in Fort Collins. During this short time, their young daughter, Hattie McDaniel, attended the Franklin School at Howes & Mountain. Hattie later found fame as a radio performer on Denver’s KOA station before moving on to pursue work in vaudeville and eventually became the first Black American to win an Academy Award for her 1939 role in Gone with the Wind. Though McDaniel is sometimes criticized for playing stereotypes of African Americans in her film roles, she is credited with paving the way for Black Americans in Hollywood.

Hattie also took part in civil rights activism. She participated in the groundbreaking 1945 “Sugar Hill” lawsuit that ended restrictive racial covenants in her Los Angeles neighborhood. McDaniel and others in the Sugar Hill lawsuit were represented by Mattie Lyle’s cousin Loren Miller, yet another connection to Fort Collins Black History.

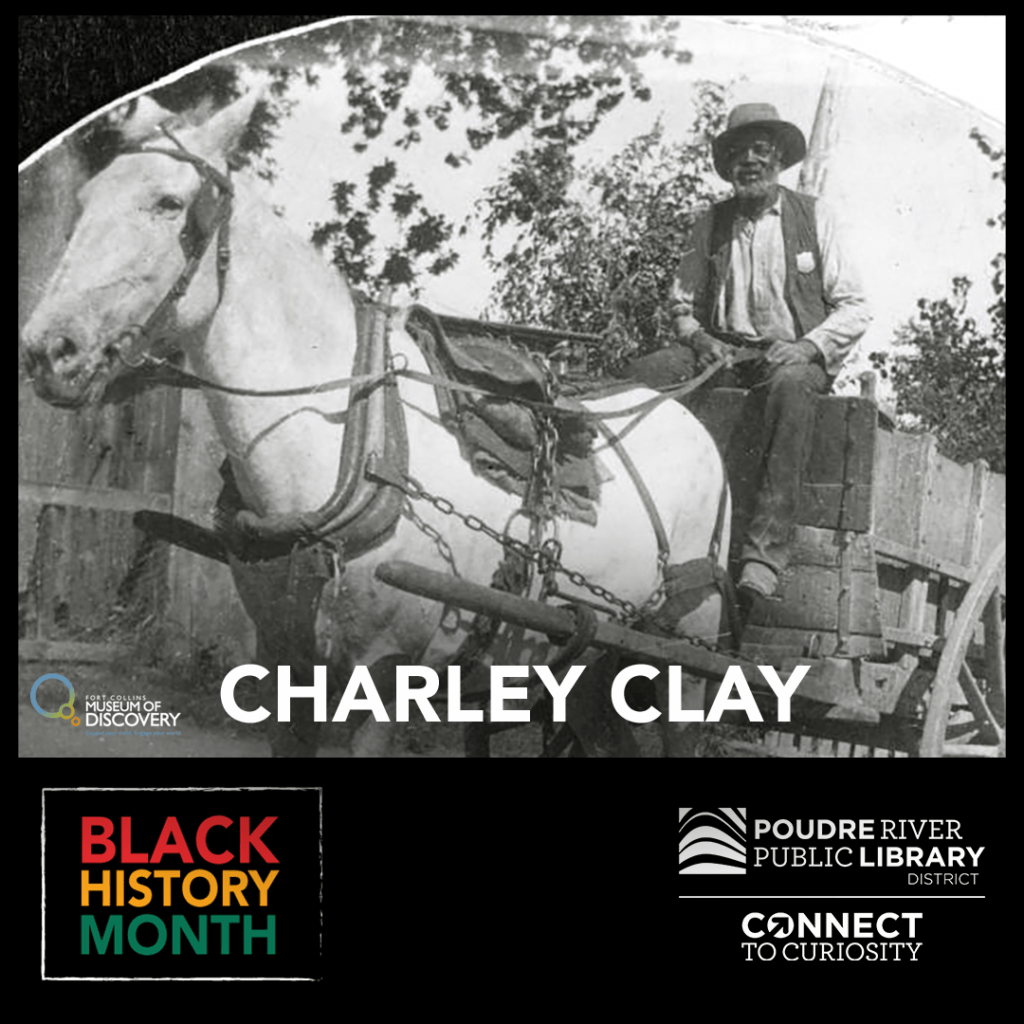

Charley Clay and The Clay Family

The Clay family was the most prominent, long-standing Black family in early Fort Collins history. Charley Clay moved to Colorado in 1864 as a cook with the military and arrived in Laporte the following year, where he found work as a barber and cook.

Clay, his wife Anna, and their 7 children also ran the Colored Mission out of his home on Maple Street. This eventually became the Zion Baptist Church and a place of worship for Black families throughout the Northern Colorado area.

Although not appearing in the 1880 census (as has been the historical trend with census counting of minority communities), Clay was well-known in the Fort Collins area. His family’s household was the place of many important social gatherings for the Black community including meetings of the local Paul Laurence Dunbar Literary Society – a national organization named for the Black poet that engaged in public discourse about social and political issues.

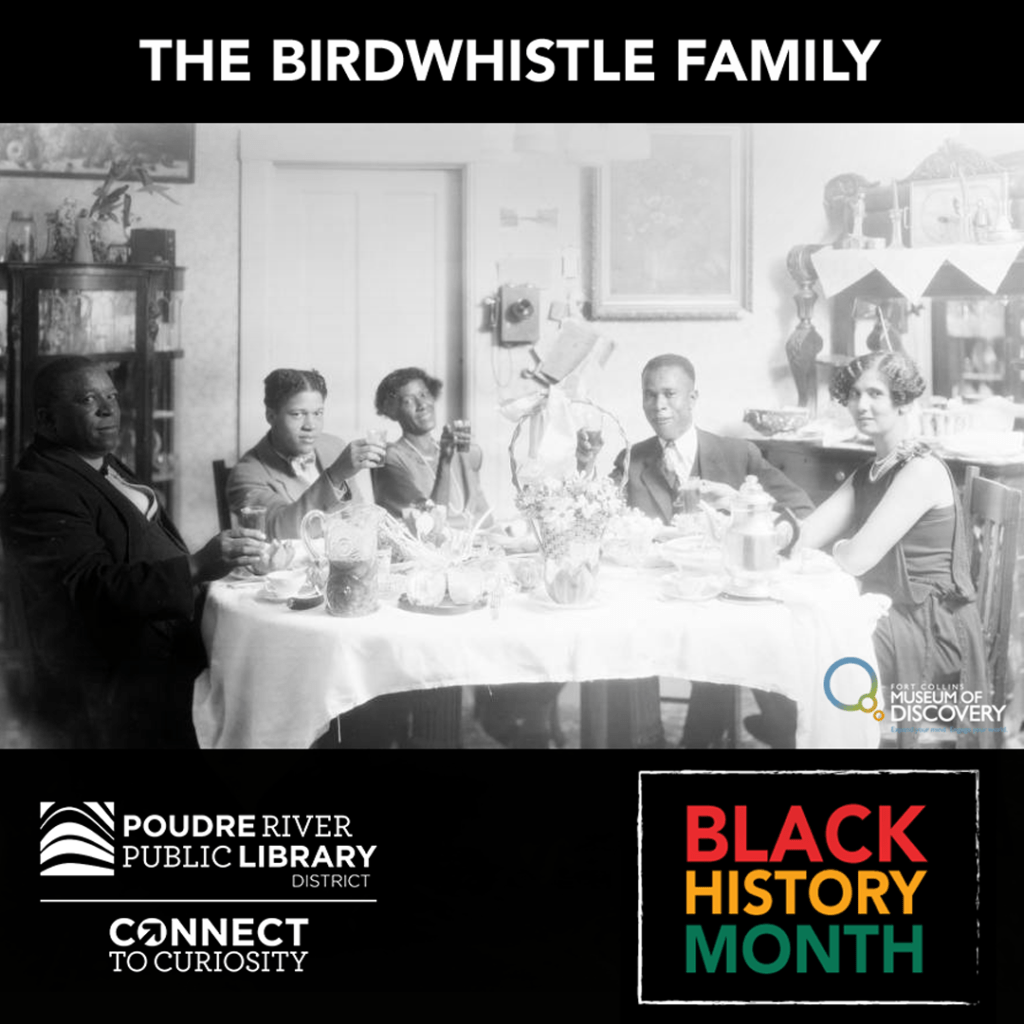

The Birdwhistles

Charles Birdwhistle grew up in a well-established Black community in Topeka, KS, and moved to Colorado along with a wave of Black Americans in the Great Migration – a massive movement of citizens fleeing from a part of their own country to escape the harsh realities of the Jim Crow South.

Birdwhistle was an educated, Spanish-American War veteran, gifted orator, performer, preacher, and community leader. Nonetheless, limited job opportunities in service positions were available to Charles in Fort Collins (like with many Black Americans who found their opportunities limited by discrimination and prejudice). He would become the headwaiter at the Northern Hotel, and janitor at the YMCA and the City’s Light and Power department. These positions ensured he was well-known to many in the Fort Collins community.

Birdwhistle and his wife, Mamie Lowe Birdwhistle, were the only black residents on their block having purchased a home on Oak Street. Their home became a local gathering place and the Birdwhistles often hosted Black scholars, orchestra members, and jazz performers as many black Americans traveling across the country would often find no accommodations available to them due to the grip of segregation throughout the country. Many were forced to rely instead on families like the Birdwhistles to take them in.

In addition to hosting travelers, Birdwhistle served as a pastor in the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Colorado, which required him to travel around the state. He turned down opportunities for permanent pastor positions to continue serving Fort Collins.

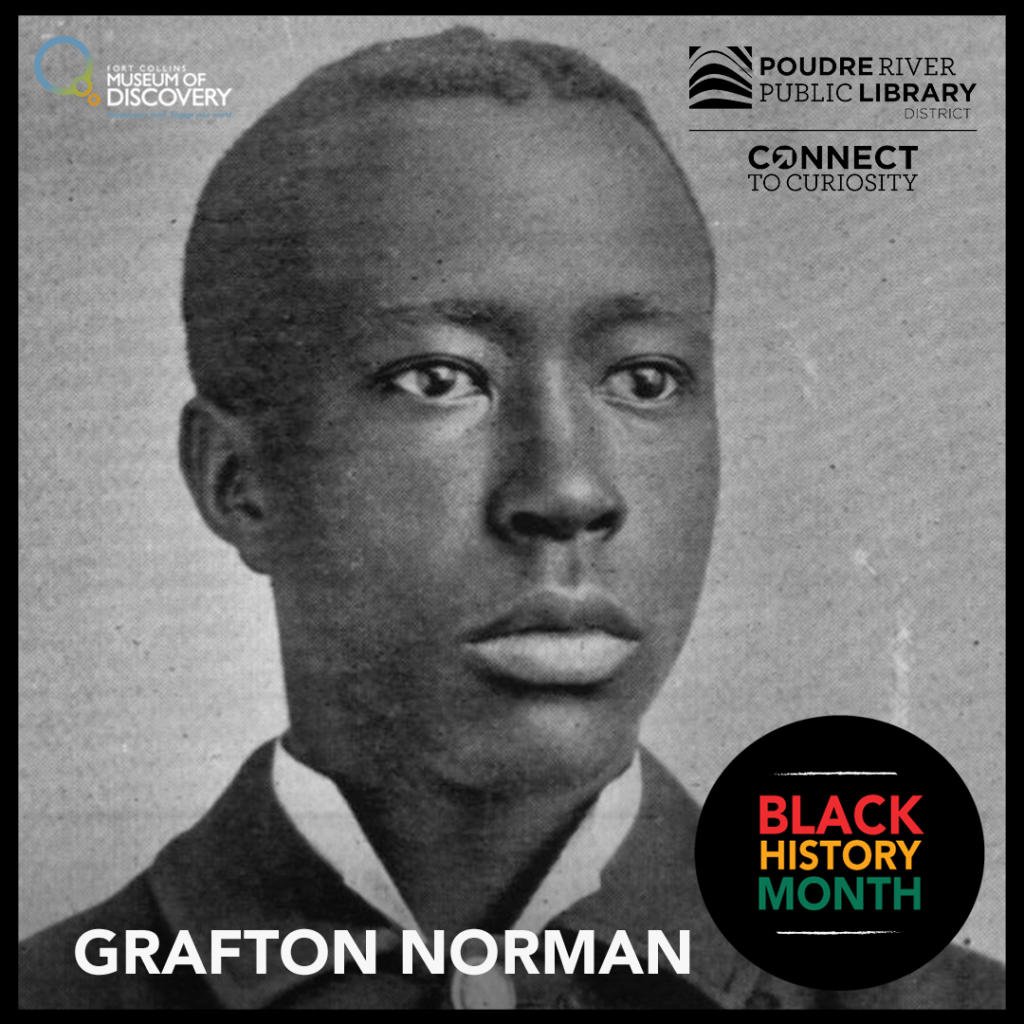

Colorado State University (then known as Colorado Agricultural College or CAC) was among the primary draws for Black Americans who moved to Fort Collins. Faced with high rates of discrimination across the Northern Colorado area, very few Black students attended CAC in its earlier years. Among the first to attend a land grant institution anywhere in the American West was Grafton St. Clair Norman.

Norman was but sixteen years old at the time he attended CAC. Norman was a highly engaged student participating in clubs like the Columbian Literary Society, the Glee Club, and the Science Club, among others. He was also a quartermaster sergeant for the College’s battalion, the precursor to CSU’s renowned ROTC training program. Norman was additionally unanimously elected by the student body to be the College orator for the celebration of Washington’s Birthday in 1896.

Grafton would later serve in the Spanish-American War and First World War in the U.S. Army. When he wasn’t serving his country, he spent his career as a math and science teacher in Alabama colleges before becoming an insurance administrator. He was later tragically killed by a driver while exiting a streetcar in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1945.

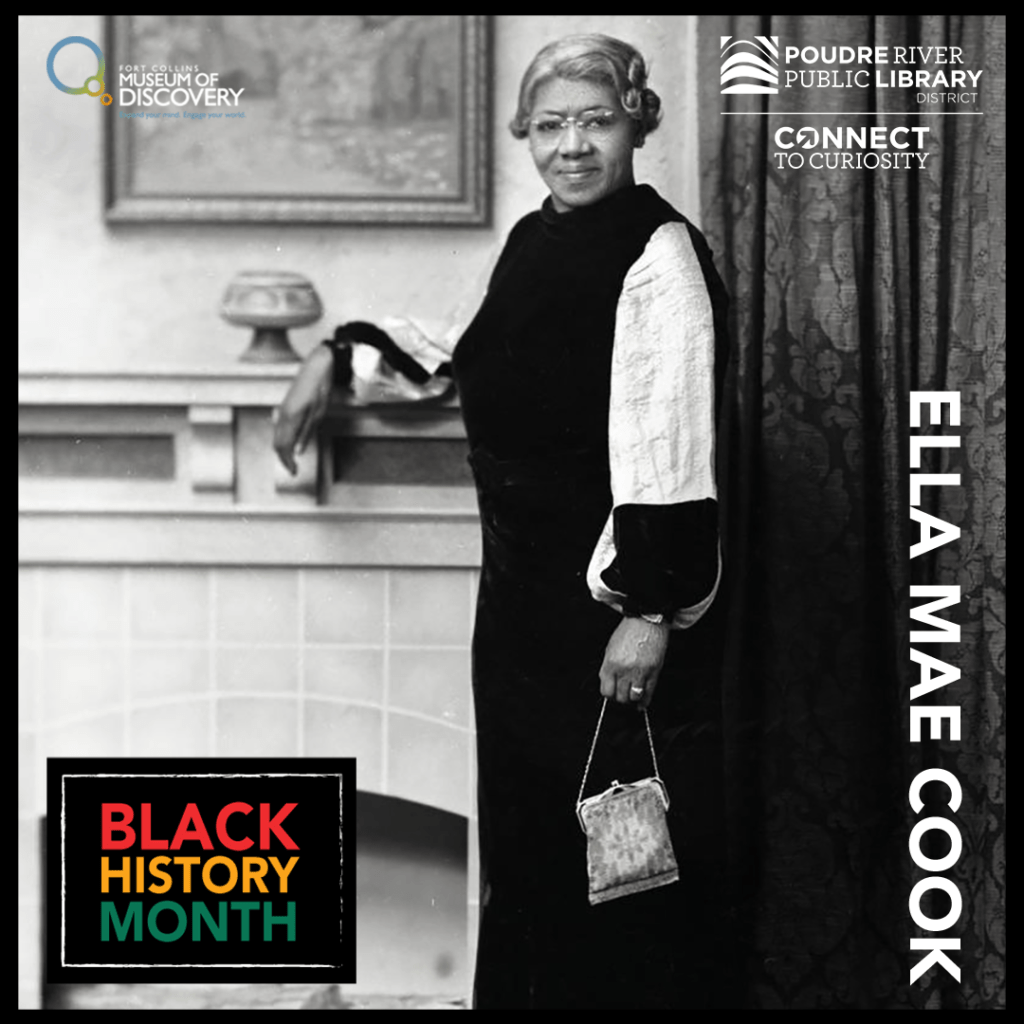

Among the important aspects of history to understand is the erasure of Black labor in places cities and towns recognize as historically important. Black experiences in important buildings and landmarks are often ignored or disconnected from these important spaces. One such place is the former home of Wild Boar café, the location on North College known as the Bradley House which was Landmarked in 2007 by the City of Fort Collins for its architectural significance.

During the 1940s when the Lear family lived in this location, Ella Mae Cook also lived in the home, working for the family as a domestic worker. Born in Eskridge, Kansas in 1887, Cook would marry Benjamin Davis in Alva, Kansas though many years later, found herself widowed. As a result, Ella Mae moved to Fort Collins and began work for the Lear family; she was one of a small number of Black domestic workers in Fort Collins for wealthier families. Black women often found domestic work one of the only avenues to earn a living due to widespread employment discrimination.

Ella Mae remarried in 1941 and together she and her new husband Alonzo Boykin moved to an apartment on S. College Ave. She passed away three years later in 1944 and was eventually buried in Denver.

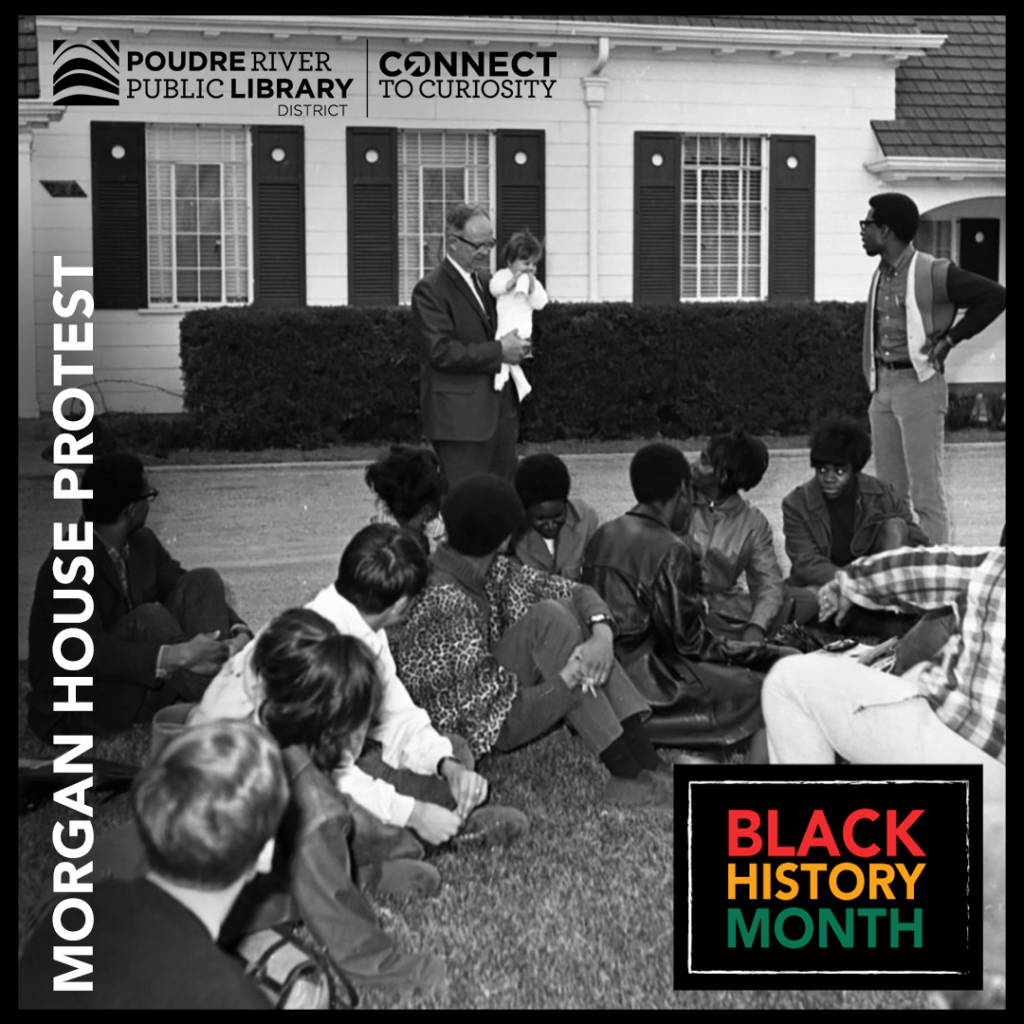

Morgan Residence Protest

One year after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Colorado State University’s Black Student Alliance (BSA) and the Mexican-American Committee for Equality (MACE) presented demands to address the lack of diversity on campus to the CSU administration. These demands were followed by a non-violent protest in front of President William E. Morgan’s residence (pictured.)

At the Morgan residence protest, students held a peaceful, all-night sit-in to highlight their cause to the community. Among their concerns was a lack of diversity among the students and staff of the University and its recruitment practices. As a result of the BSA and MACE efforts, a special minority task force was created to guide a recruitment effort focusing on Black, Chicano, and Indian students. Unfortunately, the task force did not proceed as the Colorado General Assembly and the CSU student body failed to support its funding.

This moment, and many other protests in the 60s and 70s, drove attempts for racial equity reform at CSU, some of which were met with success. To this day, the University continues to work towards making the campus a more equitable and inclusive place to work and learn.

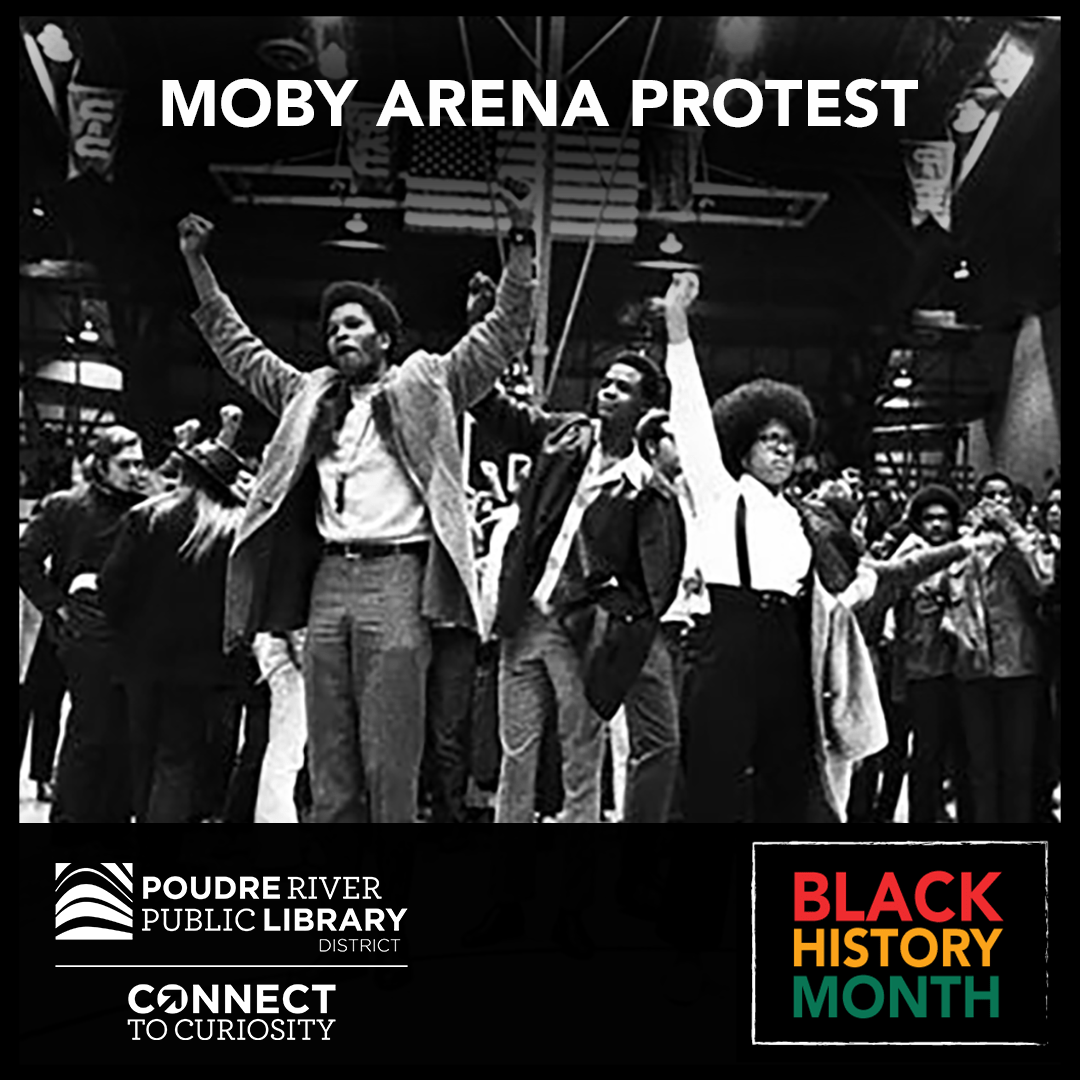

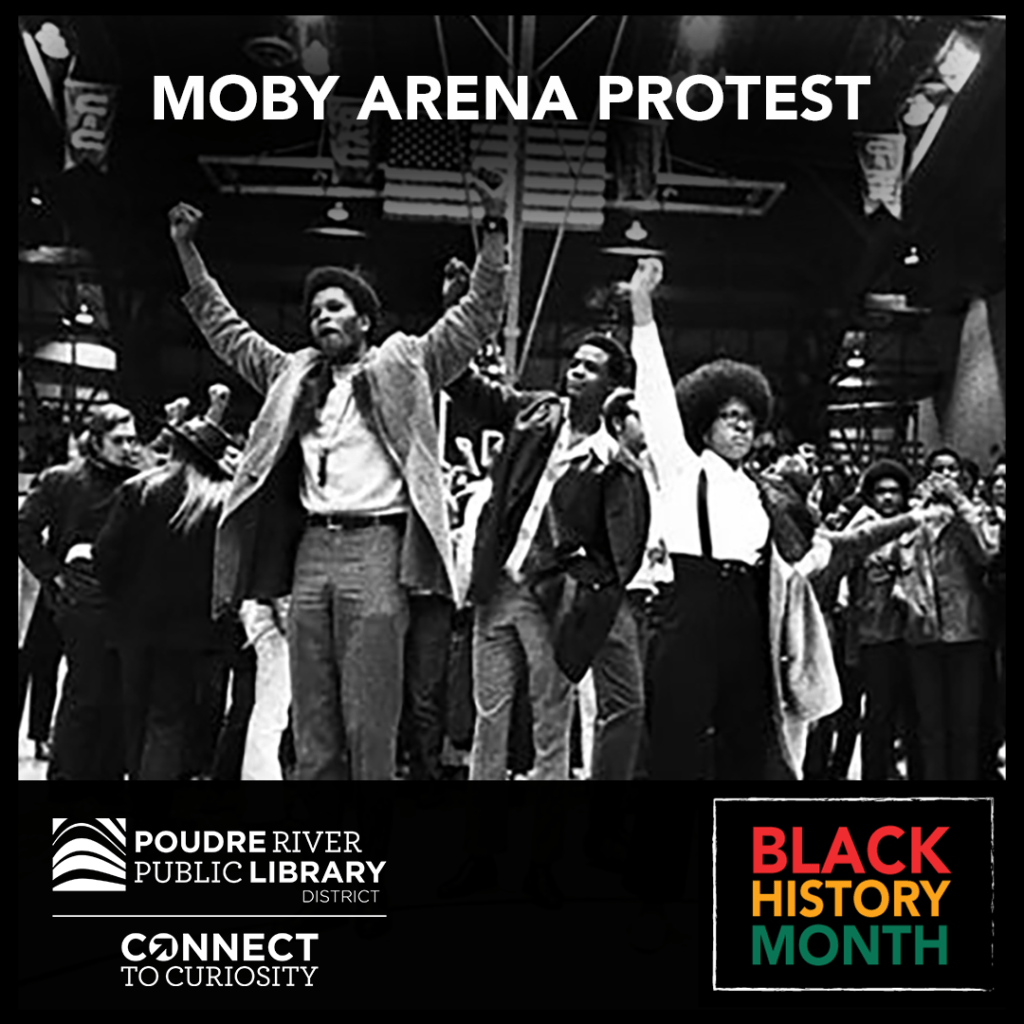

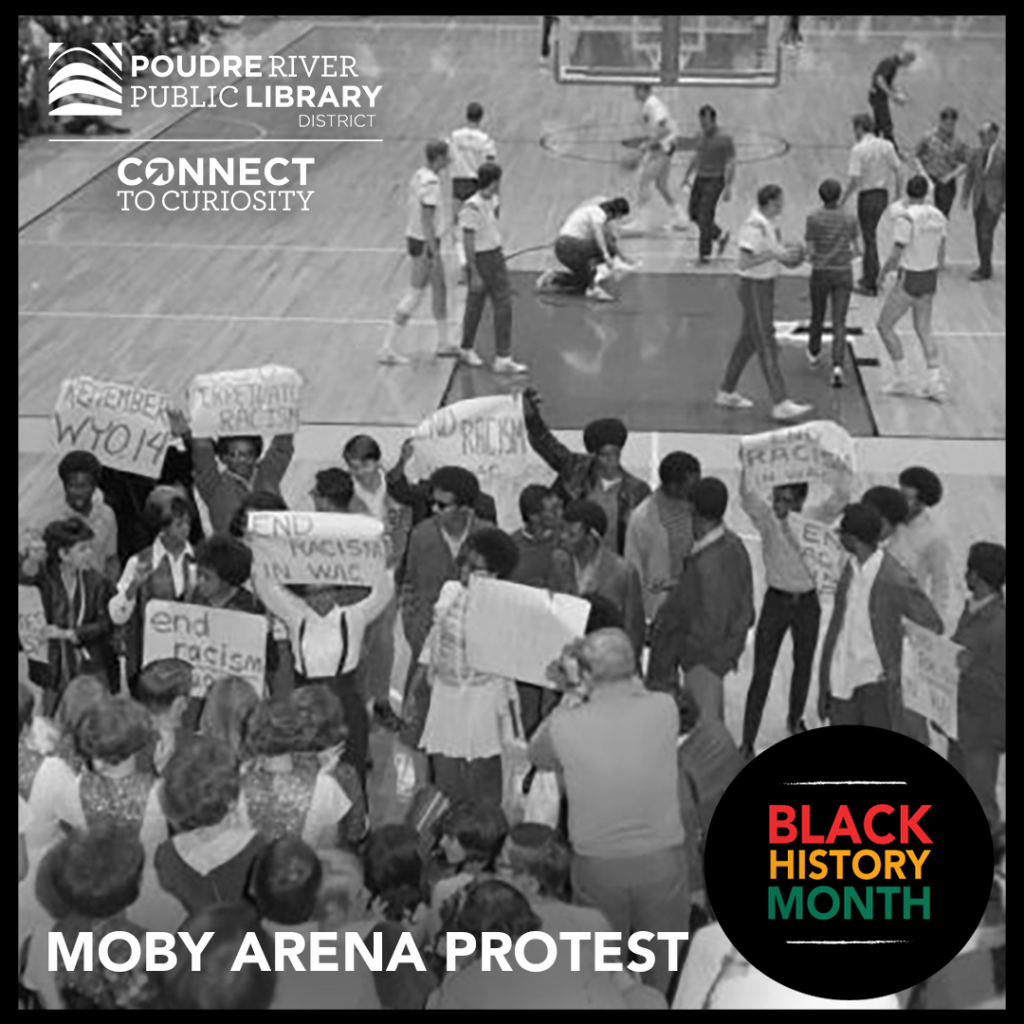

Moby Arena Protest

On February 5, 1970, African-American, Latinx, and white CSU students staged a sanctioned, non-violent, pre-game protest against the Mormon Church’s ban on allowing Black men to serve in the priesthood. The protest took place at a CSU-BYU basketball game.

When the all-white BYU team arrived to play the game, similar demonstrations were taking place on campuses across the nation. Some participants also held signs reading “Remember the Wyoming 14.” These signs referenced fourteen Black football players on the University of Wyoming’s basketball team who were dismissed by head coach Lloyd Eaton for requesting to wear black armbands in protest during the UW-BYU matchup scheduled for 1969.

Protest organizers also aimed to highlight the racial discrimination in Fort Collins, particularly housing discrimination from rental agencies and landlords who refused to lease to Black renters. When the game reached halftime, students continued their demonstration on the basketball court. When preparing to leave the court, police officers in riot gear arrived and the crowd began throwing objects at protestors.

Physical fights broke, a journalist sustained a head injury, and some students were arrested. This protest is an important historical event in Fort Collins and CSU history as we continue to make our city and its biggest university a more welcoming place for all. (Black men would officially be allowed to serve as priests in the Mormon church in 1978 and recently celebrated a 40-year anniversary of serving as priests in the LDS church in 2018.)

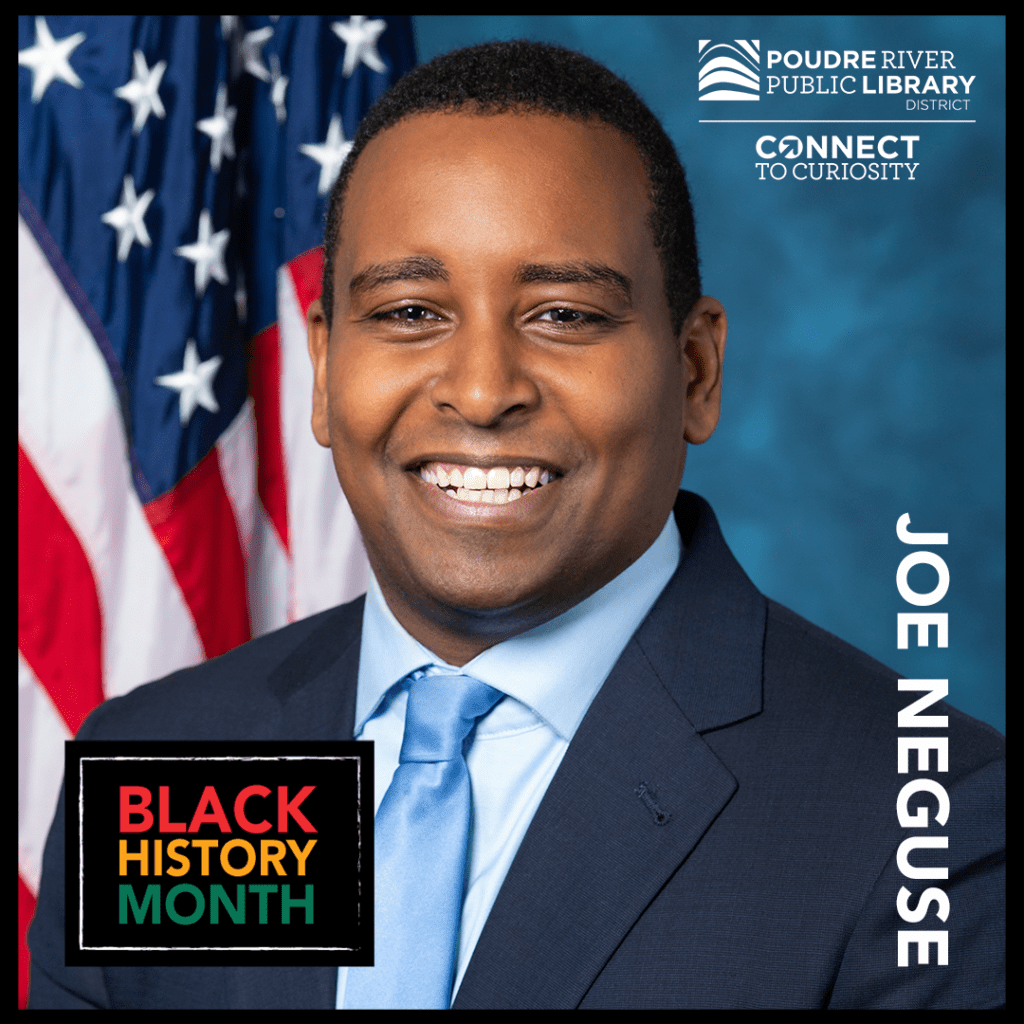

Joe Neguse

Joseph D. Neguse, born May 13, 1984, has served as the U.S. Representative for Colorado’s 2nd congressional district since 2019; he is Colorado’s first Black representative in the United States Congress. Son of Eritrean- American parents and a first generation American, Neguse is a lawyer. He serves a congressional district based in Boulder that includes the City of Fort Collins.

Neguse is a member of the Democratic Party, and was also a regent of the University of Colorado from 2008 to 2015. He was recognized as the most bipartisan member of Colorado’s congressional delegation by the McCourt School of Public Policy at Georgetown University. During his first term in Congress, he introduced more legislation than any freshman lawmaker in the country. He has had more legislation signed into law by a President than any member of Colorado’s congressional delegation.

The Center for Effective Lawmaking recently ranked Congressman Neguse among the top 10 most effective lawmakers in Congress. In his spare time, he enjoys spending time with his wife Andrea and daughter Natalie in Lafyette, Colorado where they have made their home.

Below are some staff picks for Black History Month! Enjoy your reading.

Adult Choices

Remembering Lucile by Polly E. Bugros McLeans

Frontier grit: the unlikely true stories of daring pioneer women by Marianne Monson

Buffalo Soldiers on the Colorado Frontier by Nancy K Williams

In the country of women : a memoir by Susan Straight

Crossing the line : a fearless team of brothers and the sport that changed their lives forever by Kareem Rosser (a story of the CSU Polo Team)

Black smoke: African Americans and the United States of barbecue by Adrian Miller

The president’s kitchen cabinet : the story of the African Americans who have fed our first families, from the Washingtons to the Obamas by Adrian Miller

Soul food: the surprising story of an American cuisine, one plate at a time by Adrian Miller

Guidebook to relative strangers : journeys into race, motherhood, and history by Camille T Dungy

Trophic cascade by Camille T Dungy

Suck on the marrow : poems by Camille T Dungy

All That Is Secret by Patricia Raybon

The fourth perspective : a C.J. Floyd mystery (Series) by Robert Greer

Teen Choices

Black Birds in the Sky by Brandy Colbert

Stamped From the Beginning by Ibram X. Kendi

All Boys Aren’t Blue by George M Johnson

Dark Sky Rising by Henry Louis Gates Jr.

How to Build a Museum by Tonya Bolden

The Hill We Climb by Amanda Gorman

Say Her Name by Zetta Elliott

Paul Robeson: No One Can Silence Me by Martin B. Duberman

We Are Not Broken by George M Johnson

They Better Call Me Sugar by Sugar Rodgers

Notes From a Young Black Chef by Kwame Onwuachi

Find Where the Wind Goes by Dr. Mae Jemison

Failing Up by Leslie Odom Jr.

Facing Frederick by Tonya Bolden

Lifting As We Climb by Evette Dionne

The Beautiful Struggle: a Memoir by Ta-Nehisi Coates

This is What I Know About Art by Kimberly Drew

Children’s Choices

Clara Brown : African-American pioneer = Clara Brown : pionera afroamericana by Suzanne Frachetti

Justina Ford, medical pioneer Joyce B. Lohse

Barney Ford : empresario pionero / by Jamie Trumball = Barney Ford : pioneer businessman / por Jamie Trumball

The Watsons go to Birmingham–1963 : [a novel] by Christopher Paul Curtis

Bud, not Buddy Christopher Paul Curtis

Elijah of Buxton by Christopher Paul Curtis

One crazy summer by Rita Williams-Garcia

Follow me down to Nicodemus town : based on the history of the African American pioneer settlement by A. LaFaye, illustrated by Nicole Tadgell

This is the rope : a story from the Great Migration by Jacqueline Woodson, illustrated by James Ransome

Lillian’s right to vote : a celebration of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 by Jonah Winter, illustrated by Shane W. Evans

Virgie goes to school with us boys by Elizabeth Fitzgerald Howard, illustrated by E.B. Lewis

Little leaders : bold women in black history by Vashti Harrison

Little legends : exceptional men in black history by Vashti Harrison with Kwesi Johnson

Timelines from Black history : leaders, legends, legacies by Mireille Harper]

Your legacy : a bold reclaiming of our enslaved history by Schele Williams, illustrated by Tonya Engel