It’s Black History Month! This month, we honor the unique contributions of Black individuals who shaped Colorado and recognize the discrimination, prejudice, and challenges they faced and continue to face today.

Last year, we shared the stories of remarkable Black figures in Fort Collins history. Below, are the stories of Black individuals, leaders, and communities from across the state. To explore local Black History, read our Black History article from last year.

¡Es el Mes de la Historia Negra! Este mes, honramos las contribuciones únicas de las personas afroamericanas que dieron forma a Colorado y reconocemos la discriminación y los desafíos que enfrentaron.

El año pasado, compartimos las historias de notables figuras afroamericanas en la historia de Fort Collins. De este mes, compartiremos las historias de personas y comunidades afroamericanas de todo el estado.

James H. Harvey

If you attended the MLK Day celebration at Colorado State University last month, you may have gotten an intimate view into the remarkable life of James H. Harvey – the grandfather of this year’s keynote speaker Panama Soweto. He is best known as a Tuskegee Airmen, a group of the first Black fighter pilots to serve in the U.S. military in WW11 at a time when the nation and the military were still segregated. Harvey graduated high school valedictorian and later attempted to enlist in the military in 1943. He was denied entry due to his race. Just three months later, Harvey was drafted into the military and trained as a pilot.

Despite the institutional and societal barriers set in place to challenge Tuskegee Airmen like Harvey, he completed training, served in two wars, and went on to win the U.S. Air Force’s Top Gun competition (a grueling 10-days of aerial acrobatics.) Eventually, he relocated to Denver where he lives today. He received the Congressional Medal of Honor in 2006 in addition to over a dozen other military awards over the course of his 25 years of service. In retirement, he’s an active member of Tuskegee Airmen Inc., which has raised over 1 million dollars in scholarship funds for high-performing high school graduates. He is Colorado’s last remaining Tuskegee Airman and will turn 100 years old in July 2023.

Si asististe a la celebración del Día de MLK en la Universidad Estatal de Colorado el mes pasado, es posible que hayas escuchado sobre la extraordinaria vida de James H. Harvey, el abuelo del orador principal de este año, Panamá Soweto. Es mejor conocido como uno de los Tuskegee Airmen, un grupo de los primeros pilotos de combate afroamericanos que sirvieron en el ejército de los EE. UU. en la Segunda Guerra Mundial en un momento en que la nación y el ejército aún estaban segregados. Harvey se graduó como el mejor alumno de la escuela secundaria y luego intentó alistarse en el ejército en 1943. Se le negó la entrada debido a su raza. Solo tres meses después, Harvey fue reclutado por el ejército y entrenado como piloto.

A pesar de las barreras institucionales y sociales establecidas para desafiar a los aviadores de Tuskegee como Harvey, completó el entrenamiento, sirvió en dos guerras y ganó la competencia Top Gun de la Fuerza Aérea de los EE. UU. (10 días agotadores de acrobacias aéreas). Luego, se mudó a Denver, donde vive hoy. Recibió la Medalla de Honor del Congreso en 2006 además de más de una docena de otros premios militares en el transcurso de sus 25 años de servicio. Al jubilarse, es un miembro activo de Tuskegee Airmen Inc., que ha recaudado más de 1 millón de dólares en fondos de becas para graduados de secundaria de alto rendimiento. Es el último aviador de Tuskegee vivo en Colorado y cumplirá sus 100 años en julio de 2023.

Lincoln Hills

Tucked into the mountains, Lincoln Hills is a beautiful area of the state with a remarkable history. Lincoln Hills was once the only resort for African-Americans west of the Mississippi and at the time of its founding, was just one of three resorts that specifically catered to African-Americans. In the early 1920s, Denver’s Five Points neighborhood had a booming Black population. At the same time in history, the Ku Klux Klan infiltrated Denver politics; this, in addition to pre-existing segregation, lead to increased racial tensions and race-related violence. In an effort to establish a space for Black families to come and enjoy the outdoors, Denver businessmen E.C. Regnier and Roger Ewalt founded Lincoln Hills Development Company, purchasing a large swath of land outside Denver and selling small lots to families or individuals for $50-$100. Lincoln Hills offered time in the great outdoors for Black families at a time when other recreation spaces were shaped by tangible racism and prejudice.

Obrey Wendall “Winks” Hamlet eventually founded the Winks Panorama Lodge in Lincoln Hills in 1925 and built the three-story building himself out of local materials. His lodge became a hub for outdoor recreation and community and cemented Lincoln Hills as a resort destination. Hamlet was passionate about providing opportunities for young people and fostering a welcoming culture that would go on to attract individuals and families from across the nation. He had a particular passion for engaging young people in outdoor recreation and operated the lodge until his death in 1965. After Winks’s death, the lodge was passed through many hands. Today, Wink’s Lodge is run by Lincoln Hills Cares, a non-profit that fosters environmental leadership through outdoor education and recreation for young people. The organization continues Winks’s legacy through the development and empowerment of young leaders who may not otherwise have the opportunity due to economic, social, or family circumstances. To date, the organization has served over 103,000 youth in the state. Learn more about Lincoln Hills Cares here.

Escondido en las montañas, Lincoln Hills es una hermosa área del estado con una historia notable. Lincoln Hills fue una vez el único centro turístico para afroamericanos al oeste del Mississippi y, en el momento de su fundación, era solo uno de los tres centros turísticos que atendían específicamente a los afroamericanos. A principios de la década de 1920, el vecindario Five Points de Denver tenía una población afroamericana en auge. Al mismo tiempo en la historia, el Ku Klux Klan se infiltró en la política de Denver; esto, además de la segregación preexistente, condujo a un aumento de las tensiones raciales y la violencia basada en la raza. En un esfuerzo por establecer un espacio para que la gente afroamericana viniera y disfrutara de la naturaleza, los empresarios de Denver E.C. Regnier y Roger Ewalt fundaron Lincoln Hills Development Company, compraron un terreno en las afueras de Denver y vendieron lotes pequeños a familias o individuos por $50-$100. Lincoln Hills ofreció experiencias en la naturaleza para las familias afroamericanos en un momento en que otros espacios recreativos se vieron marcados por prejuicios y racismo tangibles.

Obrey Wendall “Winks” Hamlet finalmente fundó Winks Panorama Lodge en Lincoln Hills en 1925 y él mismo construyó el edificio de tres pisos con materiales locales. Su albergue se convirtió en un centro para la recreación al aire libre y la comunidad e hizo que Lincoln Hills fuera un destino turístico. A Hamlet le apasionaba brindar oportunidades a los jóvenes y fomentar una cultura acogedora que atrajera a personas y familias de todo el país. Tenía una pasión por involucrar a los jóvenes en la recreación al aire libre y operó el albergue hasta su muerte en 1965. Después de la muerte de Winks, el albergue pasó por muchas manos. Hoy en día, Wink’s Lodge está a cargo de Lincoln Hills Cares, una organización sin fines de lucro que fomenta el liderazgo ambiental a través de la educación y la recreación al aire libre para los jóvenes. La organización continúa con el legado de Winks a través del desarrollo y empoderamiento de jóvenes líderes que de otro modo no tendrían esta oportunidad debido a sus circunstancias económicas, sociales o familiares. Hasta la fecha, la organización ha servido a más de 103,000 jóvenes en el estado. Obtén más información sobre Lincoln Hills Cares aquí.

Dr. Justina Ford

Justina Ford overcame oppression, discrimination, and prejudice to become Colorado’s first female Black physician. Born in Knoxville, Illinois, Justina showed interest in medicine from an early age and eventually attended medical school in Chicago before moving to Denver’s Five Points neighborhood around 1900 where she practiced out of her home for 50 years. Dr. Ford served any patient regardless of their race, language, gender, or ability to pay; many of her patients were those who were turned away from hospitals. Those who could not afford to pay her money would instead pay her in goods and services. Justina herself was also denied hospital privileges for most of her career, making house calls to sick patients across the city. Dr. Ford specialized as an OBGYN and delivered nearly 7,000 babies throughout her career. She was affectionately known as “The Lady Doctor” by her patients. It was not until 1950 that Justina was allowed into the Colorado and American Medical Associations at which time, she was still the only Black, female physician in Denver. She passed away in 1952 in her home which is now the Black American West Museum.

Justina Ford superó la opresión, la discriminación y los prejuicios para convertirse en la primera médica afroamericana de Colorado. Originaria de Knoxville, Illinois, Justina se interesó por la medicina desde una edad temprana y finalmente asistió a la escuela de medicina en Chicago antes de mudarse al vecindario Five Points de Denver alrededor de 1900, donde operaba una práctica en su casa durante 50 años. La Dra. Ford atendía a cualquier paciente independientemente de su raza, idioma, género o capacidad de pago; muchos de sus pacientes habían sido rechazados en los hospitales. Aquellos que no podían permitirse el lujo de pagarle dinero, en cambio le pagaban en bienes y servicios. A Justina también se le negaron los privilegios del hospital durante la mayor parte de su carrera, y tuvo que hacer visitas a domicilio para atender a sus pacientes enfermos en toda la ciudad. La Dra. Ford se especializó como obstetra y ginecóloga y atendió a casi 7000 partos a lo largo de su carrera. Sus pacientes la conocían cariñosamente como “The Lady Doctor”. No fue sino hasta 1950 que a Justina se le permitió ingresar a las asociaciones médicas de Colorado y Estados Unidos. En aquel momento, era la única médica afroamericana en Denver. Falleció en 1952 en su casa, que ahora es el Black American West Museum.

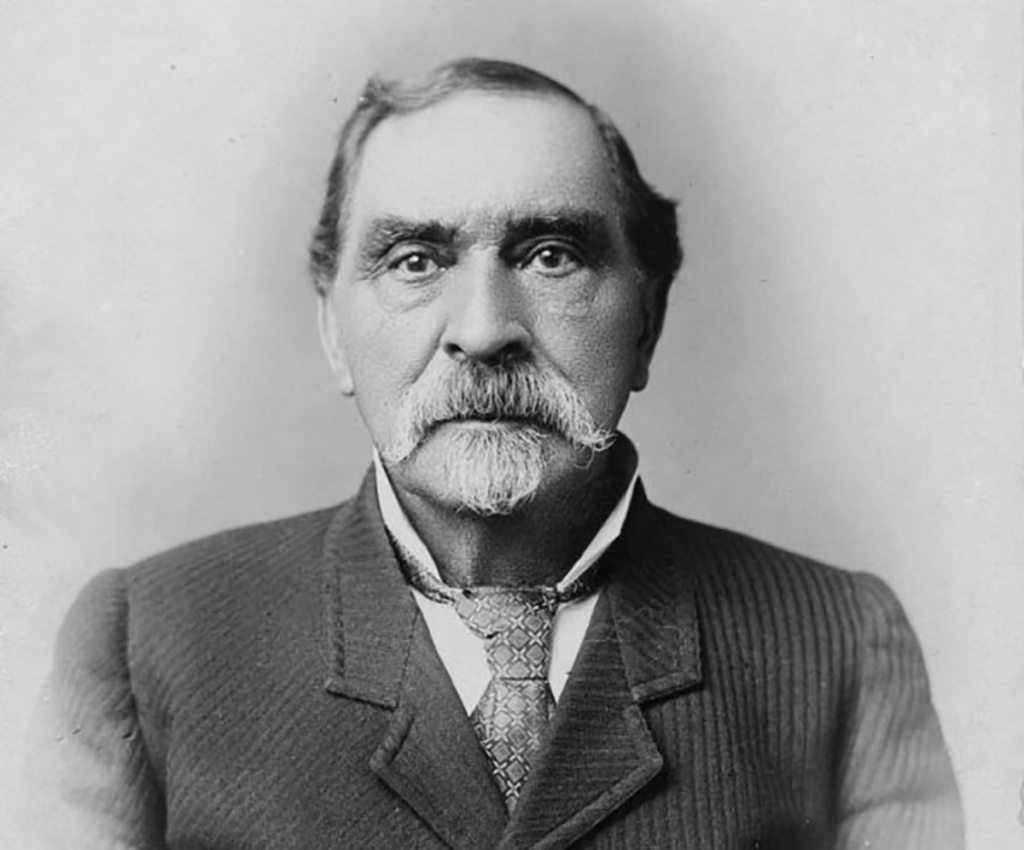

Barney Ford

Barney Ford was one of Colorado’s most successful businessmen and civil rights advocates in the late 1800s. On his path to success in business and activism, he overcame challenges, institutional barriers, and racism to become one of Colorado’s most influential citizens. Ford was born enslaved in Virginia; his father was also his enslaver. He escaped bondage in his early adulthood on the Underground Railway eventually migrating to Colorado during the Gold Rush. He staked a claim to land in Breckenridge but was later barred from claiming a stake because he was African-American. He and his wife Julia then moved to Denver where they opened a successful barber shop that later burned down in the Great Fire of 1863. Following the fire, Ford was able to acquire a loan that he used to create a restaurant and barber shop; it was so successful that he was able to pay off his $9,000 loan (equivalent to $198,073 today) in just 90 days.

He left Denver for a short time after Colorado prohibited Black men from voting in 1864. For the next several years, Ford lobbied Congress against Colorado statehood until the state covered voting rights for men of color. Thanks in part to his efforts, Colorado became the first state in the country without racialized voting restrictions written into its constitution. Barney eventually returned to the Centennial state and by the 1870s, he was one of the richest men in Colorado and the owner of several hotels and restaurants. He later opened a successful steakhouse in Breckenridge and built a home that you can still visit today for free (The Barney Ford Museum.) Beyond his business ventures, he ran an Underground Railway station in Chicago, was the first Black man nominated to the Colorado Territory Legislature, the first black man to serve on a Grand Jury in Colorado, and established a school for Black citizens in Denver. A stained-glass window depicting Barney shines light above the Speaker of the House seat in the State Capitol building, immortalizing him as one of the giants of Colorado history.

Barney Ford fue uno de los empresarios y defensores de los derechos civiles más exitosos de Colorado a finales del siglo XIX. En su camino hacia el éxito en los negocios y el activismo, superó desafíos, barreras institucionales y racismo para convertirse en uno de los ciudadanos más influyentes de Colorado. Ford nació esclavizado en Virginia; su padre fue su esclavizador. Escapó de la esclavitud en su edad adulta temprana en el Ferrocarril Subterráneo. Trabajó en todo el Medio Oeste en muchos trabajos diferentes, incluso fue dueño de un hotel por un corto tiempo en Nicaragua antes de emigrar a Colorado durante la fiebre del oro. Trató de reclamar un terreno en Breckenridge, pero fue expulsado de la ciudad y se le prohibió reclamar un terreno porque era afroamericano. Luego, él y su esposa Julia se mudaron a Denver, donde abrieron una exitosa peluquería que luego se incendió en el Gran Incendio de 1863. Después del incendio, Ford pudo adquirir un préstamo que utilizó para crear un restaurante y una peluquería; tuvo tanto éxito que pudo pagar su préstamo de $9,000 (equivalente a $198,073 en la actualidad) en solo 90 días.

Salió de Denver por un corto tiempo después de que Colorado prohibiera votar a los hombres afroamericanos en 1864. Durante los siguientes años, Ford presionó al Congreso contra la condición de estado de Colorado hasta que el estado cubriera los derechos de voto de los hombres de color. Gracias en parte a sus esfuerzos, Colorado se convirtió en el primer estado del país sin restricciones raciales de votación escritas en su constitución. Barney finalmente regresó a Colorado y, en la década de 1870, era uno de los hombres más ricos del estado y propietario de varios hoteles y restaurantes. Más tarde abrió un restaurante especializado en carnes exitoso en Breckenridge y construyó una casa que todavía se puede visitar gratis (el Museo Barney Ford). Más allá de sus negocios, dirigió una estación de tren subterráneo en Chicago, fue el primer hombre afroamericano nominado para la Legislatura del Territorio, el primer hombre afroamericano en servir en un Gran Jurado en Colorado, y estableció una escuela para ciudadanos afroamericanos en Denver. Una vidriera que representa a Barney brilla sobre el asiento del Presidente de la Cámara de Representantes en el edificio del Capitolio, inmortalizando a Barney como una de las figuras más importantes de la historia de Colorado.

Clara Brown

Clara Brown is also known as the “Angel of Rockies” and is assumed to be Colorado’s first black settler. She was born enslaved in Virginia later at age 18 and married a man named Richard who was also enslaved; together they had four children. At age 35, she was separated from her husband and children by her enslaver at an auction; she spent the rest of her life searching for her children. She was freed by her third enslaver in 1859 at which time she came to Denver during the Pikes Peak Gold Rush. Once she reached the Centennial state, Clara ended up settling in Central City where she established the town’s first laundromat. The business was fruitful and allowed her to begin investing in mines and real estate. She accrued a small fortune (~$1 million) and used it charitably, never turning anyone in need away. Clara was affectionately known by her community as “Aunt Clara.” She also began searching for her remaining child Liza Jane while helping other formerly enslaved persons in Colorado settle in the state (one of which was another one of our Black history figures, Barney Ford.) She eventually went to Kentucky to retrieve her daughter but was unsuccessful though she returned to Colorado with 16 freed men and women who she helped settle. Clara is remembered for her pioneering role in Colorado history and her remarkable life spent helping others.

Clara Brown también es conocida como el “Ángel de las Montañas Rocosas” y se supone que es la primera colona afroamericana de Colorado. Ella nació esclavizada en Virginia y a los 18 años se casó con un hombre llamado Richard que también estaba esclavizado; juntos tuvieron cuatro hijos. A los 35 años, su esclavista la separó de su esposo e hijos en una subasta; ella pasó el resto de su vida buscando a sus hijos. Fue liberada por su tercer esclavista en 1859, momento en el que llegó a Denver durante la fiebre del oro de Pikes Peak. Una vez que llegó al estado de Colorado, Clara se asentó en Central City, donde estableció la primera lavandería de la ciudad. El negocio fue fructífero y le permitió comenzar a invertir en minas y bienes raíces. Ella acumuló una pequeña fortuna (~ $1 millón) y la usó con caridad, sin rechazar nunca a nadie que lo necesitara. Clara era conocida cariñosamente en su comunidad como “tía Clara”. También comenzó a buscar a su hija, Liza Jane, mientras ayudaba a otras personas anteriormente esclavizadas en Colorado a establecerse en el estado (una de las cuales era otra de nuestras figuras de la historia afroamericana, Barney Ford). Eventualmente fue a Kentucky para recuperar a su hija, pero no fue exitoso el viaje, aunque regresó a Colorado con 16 hombres y mujeres liberados a quienes ayudó a establecerse. Clara es recordada por su papel pionero en la historia de Colorado y su extraordinaria vida dedicada a ayudar a los demás.

Julia Greeley

Julia Greeley is also known as Denver’s Angel of Charity. Julia was born enslaved between 1833 and 1848. She was liberated by the Emancipation Proclamation and later moved to Colorado in the late 1870s. Julia dedicated herself to helping the city’s poor. Nightly, she distributed resources to impoverished families in her neighborhood in a red wagon – often working at night to avoid racial persecution. When she didn’t have her own resources, she found resources by forming connections with service employees, firefighters, police officers, and more. Julia converted to Catholicism in 1880 and was very active in her congregation. She lived her life caring for others and passed away in the boarding house she resided in. It’s estimated that nearly 1,000 people attended her funeral waiting up to five hours in line to pay their respects to her. Today, she is one of six Black Americans in the canonization (sainthood) process of the Catholic Church. This is the only known picture of Julia, holding Marjorie Urquhart, a child of one of the many families she served.

Julia Greeley también es conocida como el Ángel de la Caridad de Denver. Julia nació esclavizada entre 1833 y 1848. Fue liberada por la Proclamación de Emancipación y luego se mudó a Colorado a finales de la década de 1870. Julia se dedicó a ayudar a los pobres de la ciudad. Todas las noches, distribuía recursos a las familias empobrecidas de su vecindario en un vagón rojo que a menudo trabajaba de noche para evitar la persecución de su raza. Cuando no tenía sus propios recursos, los encontró formando conexiones con organizaciones de servicio, bomberos, policías y más. Julia se convirtió al catolicismo en 1880 y fue un miembro muy activo de su congregación. Vivió su vida cuidando a los demás y falleció en la casa de huéspedes en la que residía. Se estima que casi 1,000 personas asistieron a su funeral esperando hasta cinco horas en fila para presentarle sus respetos. Hoy, ella es una de los seis afroamericanos en el proceso de canonización (santidad) de la Iglesia Católica. Esta es la única foto conocida de Julia, cargando a Marjorie Urquhart, una hija de una de las muchas familias a las que sirvió.

Ron Stallworth

Ron Stallworth’s remarkable story hails from the south of the state. Born in Chicago and later relocating to Texas and then Colorado Springs, Stallworth became the first black cadet and later detective in the Colorado Springs Police Department in 1972. He took an immediate interest in undercover police work; his most famous case was a brilliant infiltration of a Colorado Springs chapter of the Ku Klux Klan. Using his real name, Stallworth responded to a newspaper ad for new members to a regional branch. The branch’s leader at the time was a soldier at Fort Carson and Stallworth’s partner (a white officer) posed as Stallworth with the soldier during face-to-face interactions. Stallworth’s undercover investigation of the group took place over the next nine months. During this time, he infiltrated the organization’s ranks using phone calls and gaining inside knowledge on plots against minority groups in Colorado Springs. He famously framed his KKK membership card and kept it hung in his office for years. He kept this story secret for decades, first sharing it with the public in 2014 when he published his best-selling book “BlackKklansman” which was later adapted into an award-winning film. He resides today in Utah with his family. You can check out his book or the movie adaptation from our collection.

La notable historia de Ron Stallworth proviene del sur del estado. Nacido en Chicago y luego reubicado en Texas y luego en Colorado Springs, Stallworth se convirtió en el primer cadete afroamericano y luego en detective del Departamento de Policía de Colorado Springs en 1972. Se interesó de inmediato en el trabajo policial encubierto; su caso más famoso fue una brillante infiltración en un capítulo del Ku Klux Klan en Colorado Springs. Usando su nombre real, Stallworth respondió a un anuncio de periódico para nuevos miembros para una sucursal regional. El líder de la rama en ese momento era un soldado en Fort Carson y el compañero de Stallworth (un oficial blanco) se hizo pasar por Stallworth con el soldado durante las interacciones cara a cara. La investigación encubierta de Stallworth sobre el grupo se llevó a cabo durante los siguientes nueve meses. Durante este tiempo, se infiltró en las filas de la organización mediante llamadas telefónicas y obtuvo conocimiento interno sobre complots contra grupos minoritarios en Colorado Springs. Famosamente tenía encuadrada su tarjeta de membresía de KKK en su oficina y la mantuvo colocada durante años. Guardaba esta historia en secreto durante décadas, compartiéndola con el público por primera vez en 2014 cuando publicó su libro más vendido “BlackKklansman”, que luego se adaptó a una película galardonada. Reside hoy en Utah con su familia. Puedes sacar este libro o la adaptación cinematográfica de nuestra colección.

Wellington Webb

From the heart of downtown Denver to the halls of the United Nations, Wellington Webb has spent the majority of his life in public service. Webb was elected first as a Colorado state legislator, later appointed by Jimmy Carter to lead the regional department of the Department of Health, and eventually won the Denver mayoral race in 1991. His efforts shaped the Denver we know today. Webb served as Denver mayor for 12 years during which time he created more park space than any other mayor, spurred the revitalization of downtown, and helped develop bond proposals that contributed to renovations in cultural venues and libraries (including the creation of the Blair-Caldwell African American Research Library.) During his terms, Coors Field, Ball Arena (formerly the Pepsi Center), and the new Mile High Stadium were built. He also helped negotiate 25-year leases for the Nuggets, Broncos, and Colorado Avalanche. After his time as mayor, he was also appointed by President Barack Obama as a delegate to the United Nations.

As a state legislator and as mayor, Webb introduced six different bills to honor Dr. Martin Luther King in Colorado, all of which failed. His wife, Wilma Webb was also a state legislator and introduced three bills that failed to pass until finally, in 1984, the state adopted a bill to create Colorado MLK Day which has now grown to be one of the largest MLK celebrations in the country. This year, Webb spoke at the MLK celebration and parade in Denver. Today, Webb continues to enjoy retirement and lives in Colorado with his family.

Desde el corazón del centro de Denver hasta los pasillos de las Naciones Unidas, Wellington Webb ha pasado la mayor parte de su vida en el servicio público. Webb fue elegido primero como legislador del estado de Colorado, luego Jimmy Carter lo nombró para dirigir el departamento regional del Departamento de Salud y finalmente ganó la carrera por la alcaldía de Denver en 1991. Sus esfuerzos dieron forma al Denver que conocemos hoy. Webb se desempeñó como alcalde de Denver durante 12 años, tiempo durante el cual creó más espacio de parques que cualquier otro alcalde, estimuló la revitalización del centro de la ciudad y ayudó a desarrollar propuestas de bonos que contribuyeron a las renovaciones en lugares culturales y bibliotecas (incluida la creación de la Biblioteca Blair-Caldwell de investigación afroamericana). Durante su carrera como alcalde, se construyeron Coors Field, Ball Arena (anteriormente el Pepsi Center) y el nuevo Mile High Stadium. También ayudó a negociar contratos de arrendamiento de 25 años para los Nuggets, Broncos y Colorado Avalanche. Después de su etapa como alcalde, también fue designado por el presidente Barack Obama como delegado ante las Naciones Unidas. Como legislador estatal y como alcalde, Webb presentó seis proyectos de ley diferentes para honrar al Dr. Martin Luther King en Colorado, todos los cuales fracasaron. Su esposa, Wilma Webb, también fue legisladora estatal y presentó tres proyectos de ley que no se aprobaron hasta que finalmente, en 1984, el estado adoptó un proyecto de ley para el establecimiento del Día de MLK en Colorado, que ahora se ha convertido en una de las celebraciones de MLK más grandes del país. Este año, Webb fue uno de los interlocutores en la celebración y desfile de MLK en Denver. Hoy, Webb sigue disfrutando de su jubilación y vive en Colorado con su familia.

Below are some staff picks for Black History Month. Enjoy your reading!

Adult Choices

Remembering Lucile by Polly E. Bugros McLeans

Frontier grit: the unlikely true stories of daring pioneer women by Marianne Monson

Buffalo Soldiers on the Colorado Frontier by Nancy K Williams

In the country of women : a memoir by Susan Straight

Crossing the line : a fearless team of brothers and the sport that changed their lives forever by Kareem Rosser (a story of the CSU Polo Team)

Black smoke: African Americans and the United States of barbecue by Adrian Miller

The president’s kitchen cabinet : the story of the African Americans who have fed our first families, from the Washingtons to the Obamas by Adrian Miller

Soul food: the surprising story of an American cuisine, one plate at a time by Adrian Miller

Guidebook to relative strangers : journeys into race, motherhood, and history by Camille T Dungy

Trophic cascade by Camille T Dungy

Suck on the marrow : poems by Camille T Dungy

All That Is Secret by Patricia Raybon

The fourth perspective : a C.J. Floyd mystery (Series) by Robert Greer

Teen Choices

Black Birds in the Sky by Brandy Colbert

Stamped From the Beginning by Ibram X. Kendi

All Boys Aren’t Blue by George M Johnson

Dark Sky Rising by Henry Louis Gates Jr.

How to Build a Museum by Tonya Bolden

The Hill We Climb by Amanda Gorman

Say Her Name by Zetta Elliott

Paul Robeson: No One Can Silence Me by Martin B. Duberman

We Are Not Broken by George M Johnson

They Better Call Me Sugar by Sugar Rodgers

Notes From a Young Black Chef by Kwame Onwuachi

Find Where the Wind Goes by Dr. Mae Jemison

Failing Up by Leslie Odom Jr.

Facing Frederick by Tonya Bolden

Lifting As We Climb by Evette Dionne

The Beautiful Struggle: a Memoir by Ta-Nehisi Coates

This is What I Know About Art by Kimberly Drew

Children’s Choices

Clara Brown : African-American pioneer = Clara Brown : pionera afroamericana by Suzanne Frachetti

Justina Ford, medical pioneer Joyce B. Lohse

Barney Ford : empresario pionero / by Jamie Trumball = Barney Ford : pioneer businessman / por Jamie Trumball

The Watsons go to Birmingham–1963 : [a novel] by Christopher Paul Curtis

Bud, not Buddy Christopher Paul Curtis

Elijah of Buxton by Christopher Paul Curtis

One crazy summer by Rita Williams-Garcia

Follow me down to Nicodemus town : based on the history of the African American pioneer settlement by A. LaFaye, illustrated by Nicole Tadgell

This is the rope : a story from the Great Migration by Jacqueline Woodson, illustrated by James Ransome

Lillian’s right to vote : a celebration of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 by Jonah Winter, illustrated by Shane W. Evans

Virgie goes to school with us boys by Elizabeth Fitzgerald Howard, illustrated by E.B. Lewis

Little leaders : bold women in black history by Vashti Harrison

Little legends : exceptional men in black history by Vashti Harrison with Kwesi Johnson

Timelines from Black history : leaders, legends, legacies by Mireille Harper]

Your legacy : a bold reclaiming of our enslaved history by Schele Williams, illustrated by Tonya Engel